Yemen’s Architecture of the Future

The architecture of Yemen, with its multi-storey towers and domes of mud brick, is under constant threat of destruction – but a new book aims to tell the story of its beauty and radicalism.

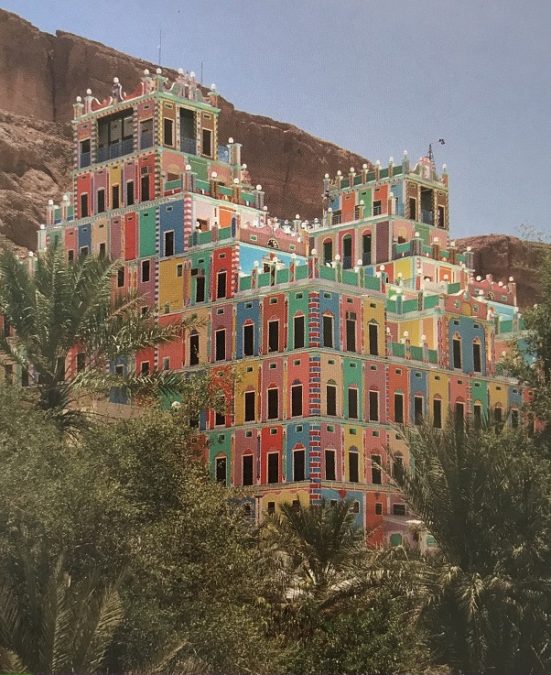

Traditional houses in Shibam. Credit: Hatchette.

‘This is the architecture of the future, not the past’

– Daw’an Mud Brick Architecture Foundation, 2013

From the intricate traditional facades of Sana’a and Yafi’ to the colonial architecture of Aden and the mud brick conurbations of Hadramut, the architect and historian Salma Samar Damluji takes the reader on a unique and rare journey into a culture and region that many will never witness first-hand. The domed tombs of the Saints and the Buqshan Palace stand out as jewels in this ambitious and rigorous manifestation of a lifetime’s worth of research into Yemeni architecture and building culture.

The book starts at the coast, in the ex-British colony of Aden, and works its way inward to the north and the east covering Lahij, Al Shu’ayb, Jiblah, Yafi’, Bayhan, Habban, and Hadramut, including Al Mukalla, Wadi Hajr, Wadi Daw’an, and Shibam. The author describes, compares, and analyses in detail the various forms, materials and techniques used in the different cities. She uses architectural conventions such as plans, sections, elevations and axonometrics as well as photographs to convey case studies as architectural paradigms of the region. Each section is instigated by a quote from a notable figure or institution that contextualises the contemporary condition and its relationship to the past.

Despite being of Yemeni heritage myself, I have never visited, due to both the country’s unstable political condition and my detachment from its culture. I grew up thinking of it as a primitive part of my heritage, a place where family members would visit in preparation of arranged weddings, to find suitable wives. For the male members of the family, visiting is a rite of passage during adolescence – they would spend time in the desert, praying and learning to shoot a gun, miraculously transcending boyhood. It wasn’t until after I began my architectural training that I understood its value as architectural knowledge. I share the author’s criticism of mainstream architecture’s marginalisation of its potential as a contemporary language for Middle Eastern and Arab architecture. New burgeoning nations such as the United Arab Emirates might have continued and evolved the legacy of earth and stone skyscrapers in the region, rather than ignoring their inherent intelligence, beauty, and wisdom.

Damluji’s urgency in wanting to share this book as a necessary resource for both the Yemeni and global architectural and construction community is palpable. The ongoing civil war that started in 2014 continues to destroy the country’s ancient and unique architectural heritage; the United Nations describes it as ‘the largest humanitarian crisis in the world’. The lack of architecture schools and funds within the country creates a precarious situation in which the transfer to future generations of the intelligence embodied in the nation’s building culture and its master builders is uncertain. There is a need for a thorough catalogue of materials and construction techniques that will allow this knowledge, craft, and skill to be transferred and restored, if not now, later. Furthermore, the urgency of the current climate crisis has shown a resurgence in the need to understand how to build with low carbon materials such as earth and stone, for the continual creation of climatically comfortable as well as sustainable cities.

The Architecture of Yemen and its Reconstruction is a new edition of Damluji’s Architecture of Yemen, From Yafi to Hadramut, released in 2007. Here, the book revisits particular case studies that have since been destroyed in more detail, while reflecting and documenting several restoration projects that the author has been involved in since, through national and international funding institutions. In doing so, she explains the process of working with the community to rebuild and enhance their quality of life, in addition to restoring value and faith in the country’s built heritage.

The author’s determination to convey the acumen of the master builders by highlighting interviews with them in each section—as well as the use of Arabic words, communicating both their pronunciation and meaning—explains her in-depth understanding of the subject matter, making the research sui generis. Master builders are defined as the craftsmen and builders who have acquired an unparalleled and often arcane grasp of their trade, rightfully referred to as ‘true interpreters of their culture’. To me, this is testament to the importance of valuing craft and embodied knowledge as well as the importance of language in communicating a culture and its surrounding edifices. Salma Samar Damluji goes so far as to include a glossary of Arabic terms explaining their meaning, creating a specific translatable architectural diction that would otherwise remain as oral resource transferred through the vocation and practice of building.

In his 1973 short film The Walls of Sana’a, Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini proclaimed that the reverence for heritage in Italy is gone, but that there is still hope in Yemen. If that is still to be the case, Yemen needs to value and care for its ancient built environment. Damluji offers avenues and insights into ways of doing this for its public, its inhabitants, and posterity. Even though I agree with this in principle, it is still unfortunate that edifices as artefacts alone cannot offer citizens a complete experience. Yemen’s cities still need an infrastructural resolution that is lacking, including political, healthcare, and educational frameworks and safety for its population, if it is to have any hope of regaining the economic independence that will allow it to thrive as a nation.